Beijing and the Provinces: Geographic Disparities Among CCP Elites

Introduction

Conventional Western analysis tends to view China – and especially Han China – as a monolith. Yet, the strong regional disparities that mark the Chinese central government shape Beijing’s behavior and U.S.-China relations. For instance, uneven representation of Chinese provinces among political elites points to persistent lines of internal fracture inherited from imperial times that are blind spots in conventional analyses of contemporary China.

Overview

Every five years, new members of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) are selected. The Central Committee is a body composed of the 200 top leaders in the country, including Politburo members and General Secretary Xi Jinping. With a new Central Committee to be named following the next Party Congress in fall 2022, Baron has conducted an analysis of the membership of recent Central Committees, exploring members’ province of origin.

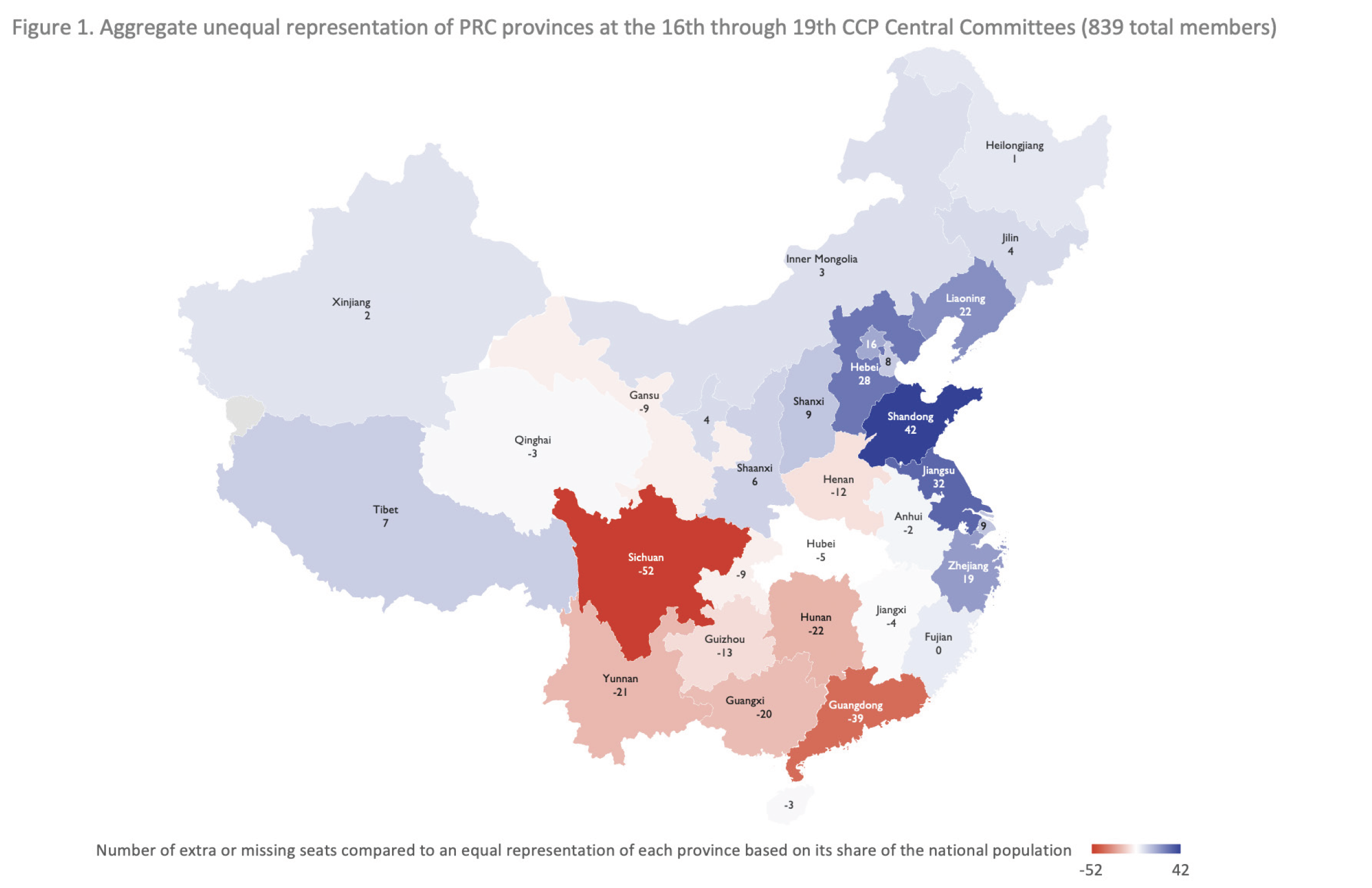

This analysis reveals a striking disparity: coastal provinces between Beijing and Shanghai are overrepresented, and southern provinces between Sichuan and Guangdong underrepresented.

This pattern echoes the power distribution of imperial times, suggesting that certain political aspects of China have changed little in the past century. For U.S. strategists and policy makers seeking to shape the future of bilateral relations, understanding these regional disparities could prove key.

Beijing-Shanghai vs. Chengdu-Guangzhou Axes

Many analyses of the Central Committee assign members to “factions” based on the relationship networks that members formed when working for the administration of a given city or province at the same time as a future CCP top leader.1 For instance, the Central Committee is filled with individuals whose promotion to the party’s elite circles can be traced back to ties they forged working with Xi Jinping when he was Governor of the provinces of Fujian (1985-2002) or Zhejiang (2002-2007).

This approach overlooks, however, an important factor: place of ancestry. An analysis of this factor reveals that the coastal provinces from Beijing to the Shanghai region are significantly overrepresented compared to their relative share of China’s total population (see Figure 1).2 The Chengdu-Guangzhou axis in the south and southwest of the country, particularly the populous Sichuan and Guangdong provinces, is markedly underrepresented. The northern and western border regions, including those with significant minority populations such as Tibet and Xinjiang, are all fairly represented relative to population.

The overrepresentation of CCP elites from the central and northeastern coast could be expected based on the wealth concentrated there. If representation were linked to economic development, however, then Guangdong should also be overrepresented: it is the wealthiest Chinese province today and has been an economic powerhouse since the opening of trade with the West during the 19th century. Guangdong’s stark underrepresentation suggests that the explanation for this pattern must be found elsewhere.

Imperial Heritage

This present-day pattern of political influence among Chinese provinces aligns better with China’s long tradition of centralized civil administration and power distribution.

Historically, the Chinese heartland has been located in the Yellow River valley and the Yangtze Delta. Succeeding dynasties have always established their capital city at the edge of this region: Nanjing on its southern end for dynasties with a power base in the Yangtze Delta, Xi’an or Luoyang in the mountains that form its western border for dynasties fearful of western kingdoms, and Beijing in the North for dynasties established by northern invaders.

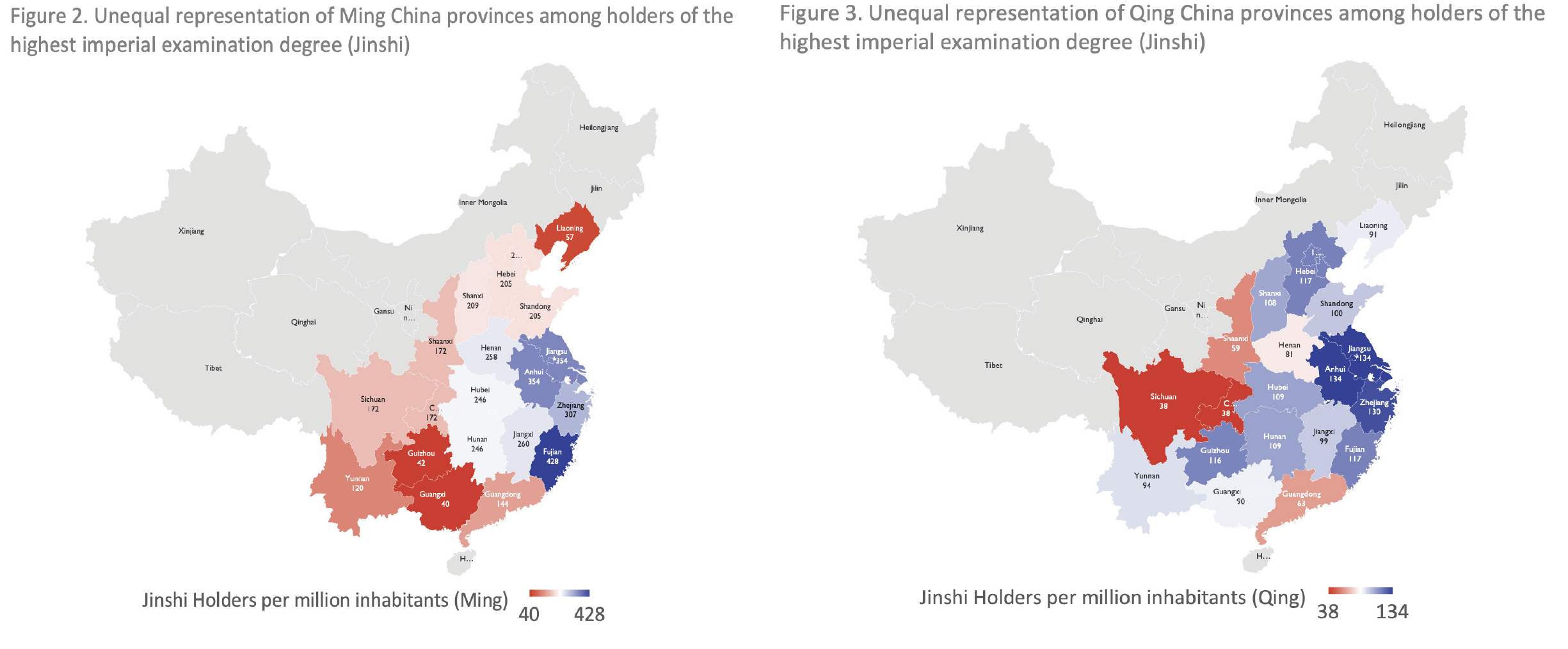

As a result, Chinese emperors, ministers and generals have almost all come from this heartland, while Sichuan and Guangdong have rarely played an important political role despite their early integration into the Chinese realm, when it was first unified by the Qin dynasty around 200 BC. Figures 2 and 3 show the number of Jinshi degree holders (the highest administrative degree) per province during the Ming and Qing dynasties.3 Just as in the Central Committee today, the majority of Chinese imperial elites during the last five centuries had roots in the region between Beijing and Shanghai, with relatively few coming from the southern and southwestern regions.

Implications

The overrepresentation of Chinese government elites from eastern coastal provinces illustrates the often-underestimated influence of long-term dynamics inherited from previous historical periods. The Middle Kingdom’s recent fast-paced economic growth has not fundamentally modified certain core characteristics of imperial China: beneath the gleaming new airports, high-speed rail, and other external markers of the advent of a new China, old patterns persist.

Regional dynamics should play a key role in the efforts of those seeking to forecast and shape the future of U.S.-China relations. Despite General Secretary Xi Jinping’s emphasis on the importance of the CCP’s role in creating national unity, China remains a country shaped by internal fractures and differentiation.4 U.S. decision makers should be prepared for these regional divergences to continue to drive leadership dynamics and outcomes.

Endnotes

1 See, for instance: Guoguang Wu, “The King’s Men and Others: Emerging Political Elites under Xi Jinping” China Leadership Monitor, June 1, 2019, https://www.prcleader.org/wusummer; Srijan Shukla, “The Rise of the Xi Gang: Factional Politics in the Chinese Communist Party,” Observer Research Foundation, February 12, 2021, https://www.orfonline.org/research/the-rise-of-the-xi-gang.

2 The data for this map was collected from Macro Polo’s “The Committee” project (https://macropolo.org/digital-projects/the-committee) in the case of the 19th Central Committee, and from the Chinese-language versions of the 18th, 17th, and 16th Central Committees Wikipedia pages, as well as those corresponding to each member. For each Central Committee, the actual number of members whose ancestry is located in a given province is compared to the number of members that would have been assigned to that province if seats were distributed based solely on its share of the country’s population in 1954 (most members of the 16th through 19th Central Committees were born in the 1950s). The final map, which combines the results for each of the four analyzed Central Committees, was created by adding these differences per province across all four of them.

3 The data used to create these two maps comes from the following source: Benjamin E. Elman, A Cultural History of Civil Examinations in Late Imperial China, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000, 696-700.

4 See, for example: “Full text of Xi Jinping’s speech on the CCP’s 100th anniversary,” Xinhua via Nikkei Asia, July 1, 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Full-text-of-Xi-Jinping-s-speech-on-the-CCP-s-100th-anniversary.